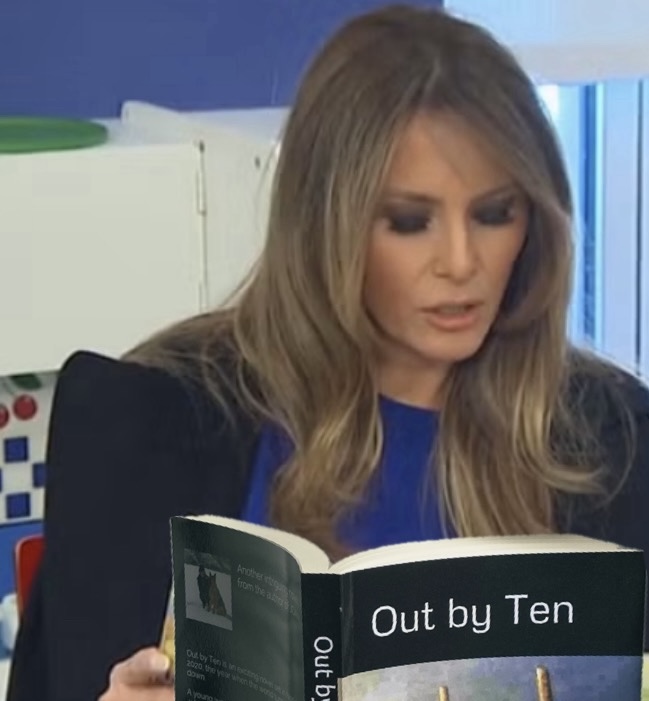

Out by Ten

by Anne E. Thompson

Chapter One

I didn’t begin to feel safe until I reached Norwich. As the train heaved towards the platform, with a great screeching of wheels and complaining of brakes, it was as if I had been holding my breath and finally, with a sigh, allowed myself to think that perhaps I had managed to escape after all. While we slowed, a conveyor-belt of painted faces peering in, I joined the general shuffling of the masses and edged towards the doors. People were staring at suitcases stored near the exit, ensuring no one stole them, mothers were gathering a plethora of plastic toys and sweeping sweet wrappers over the edge of the grey tables so they fell like confetti to the carpet below, men in crumpled suits with tired faces were clutching briefcases and over-night bags. We inched forwards, any bond formed during the journey through smiles or the fleeting meeting of eyes was now dissolved, we moved individually, each person isolated from the other passengers, until finally, with a giant step down from the carriage, we were free.

I moved cautiously, looking for security cameras. I chose two boys, one with chaotic hair and a blue coat, his friend wearing a beanie and carrying a backpack, and stayed as close to their backs as I could. Anyone watching would have thought we were together, student friends returning to Norfolk, off to find a taxi together. The yellow barriers were all left open, so I shoved my redundant ticket into a back pocket and walked in the footsteps of my unsuspecting buddies as we left the canopied platform, past the Starbucks and the single policeman staring aimlessly into space. It was the end of the morning commuting time, and a few people in business suits were still hurrying to work. There was a child wearing pink bunny ears chewing a breakfast donut, spilling crumbs as she ate. A man, walking while he read a text almost walked into two girls as they emerged from M&S carrying their tiny bag of food. Everyone was in their own isolated capsule, and I felt invisible as we headed towards the Victorian red brick wall of the main concourse. As we neared the ticket office, I peeled off, said a silent farewell to my pretend friends, and stood in line at the automatic ticket machine.

I knew the timetable by heart – weeks of planning and surreptitious trips to the library to use the computer ensured I was prepared, and when it was my turn, I bought a single ticket to Sheringham. A man was standing behind me, and although I knew he was probably simply waiting his turn, he made me nervous, and I tried to cover the screen, to hide where I was going, in case he remembered later and repeated the information. I heard him sigh when I pulled out money – I knew he was impatient, surprised that I wasn’t using a card, which was surely what the machine was designed to receive. But I couldn’t risk using cards, couldn’t risk being traced, so I ignored him, and smoothed out the crumpled notes as best I could, and fed them laboriously into the slit designed for paper money. The machine whirred. Coins clinked into the bottom section, followed by the orange ticket and matching receipt. I pushed back the plastic flap and retrieved my things, clutching them in my hand as I moved away. I glanced up at the departures board, checking the times splashed in orange letters matched the information in my head.

The public toilets had the same damp chemical stale air as all other public toilets in England. The same middle-aged women were washing their hands while checking their hair in the mirror, the ubiquitous harried mother was trying to stop her three-year-old touching every surface, and handle, and wall; while a teenager smeared eye-liner around the rim of her eyes. I crossed the wet floor, edged past the yellow plastic “cleaning in progress” warning placard, and locked myself into a cubicle. Which is when I actually, for a moment, properly relaxed.

People assume that being a prisoner is all about locks – being locked into a space by someone else and not being allowed to leave. But actually, the reverse is as heavy a burden. Unless you are free, the ability to lock yourself into a place is also denied. The prisoner is unable to lock a door, to shut out the world, to enclose themselves into a space that is truly private. They are always on view, watched, analysed – whether they are aware of it or not. I leant back against the door and closed my eyes, savouring the precious moment of being unobserved, hidden from the world. No one knew where I was, no one was watching, I was truly, wonderfully, alone. But only for a few minutes.

When I emerged, walking straight to the row of damp sinks, there was a woman with two daughters standing by the driers. They were Chinese – or some similar ethnicity – and while they shook drips from their hands and spoke in their sign-song chatter, I noticed how similar the two girls were. Separated by a couple of years, one was taller, but that was the only difference I could discern, they seemed identical. Both were laughing, their dark eyes dancing beneath thick fringes of black hair, wide lips drawn back to show their small straight teeth. They were pretty, with their slim bodies and smooth skin, and as they giggled and chatted, they drew the attention of the other women using the washroom. Two identical dolls. I wondered what it would be like, to grow up with someone so similar in appearance as to be almost interchangeable, to potentially, when the height differential lessened, have a physical substitute at hand. I smiled briefly, exploring in my mind the wonderful freedom of being able to ask another person to take my place, to never be missed, because someone else was fulfilling my obligation. It would, I felt, be the most wondrous thing ever.

But then, as the pair moved away from the purring drier and turned towards the exit, both swishing long black plaits down their slim-shouldered backs, I realised that to have a substitute, they must first be willing. To have someone take my place in life, would involve giving up their own, and that, I knew, would be an impossible ask. No one, I thought, would willingly give up their own happiness simply to fulfil the dreams of another. The girls left, and I moved to take their place, holding my hands under the warm flow of air until they were dry.

I kept an eye on the time, moving back to the platforms when my train was due to leave. I chose a seat near the front, thinking that when we reached Sheringham, I could be out and away before most other people had alighted, and that a ticket inspector, if there was one, would be watching the masses as they stepped from the train, and would barely focus on the first few passengers to hand him their tickets.

I found a seat near a window, and moved my bag next to me, closing my eyes so that people would think I was asleep and would choose somewhere else to sit. The train was rumbling in the way that only diesel trains are able, that gradual warming up hum, the sound of an over-stretched engine which is trying to find the gears. I opened my eyes when the train jolted into motion, and looked around the carriage.

The train was fairly empty, the only person who could see me was an elderly lady, who sat in the seats opposite. She had a fat shopping bag, with groceries spilling from the top, and a small brown handbag which she moved from her knee to the empty seat next to her. She smiled at me when I glanced towards her, and opened her mouth as if to speak, so I turned quickly back to the window, and watched as the city was replaced by fields and bushes and lines of trees that rushed past in an endless line of green and brown.

“Excuse me.”

I looked across the aisle. The elderly woman had removed her coat and headscarf, and was leaning towards me, waiting. I nodded, sighing inwardly. Old ladies seem to enjoy talking to young women; I tried to appear discouraging.

“I wonder if you would be very kind and watch my things for me,” she was saying, her face creased into a smile, her eyes trusting. “I need to use the ladies’ room, and I was wondering if you could watch my bags while I’m gone? So no one touches them?”

I stared at her, took in her blue-grey hair, the kind eyes behind the wire-rimmed glasses. We were strangers, two people who happened to choose the same carriage to sit in, but apparently, that was the only criteria necessary for her to trust me. Or perhaps it was because I was female, and there was some unwritten code which meant that she could trust me, someone who shared her gender, that I as a woman would ensure her bags were safe. Maybe in her era, young people were more honest.

I opened my mouth, not sure how to respond, wanting to warn her, to protect her from the dangers of trusting strangers; then closed it and nodded.

“Thank you so much dear. I shan’t be long.”

I watched as she stood, she waited a moment to find her balance as the train swayed, then walked towards the doors at the end of the carriage. They clicked shut behind her departing back.

I looked across the aisle. There was her coat: brown, not new, neatly folded, topped by the square of her red headscarf. On the seat next to them was her handbag – her handbag – presumably containing her purse, possibly her house key, probably stuffed with old receipts, and a tissue and a pen, maybe even a phone. I thought for a long moment about that phone, savouring the possibility of it, the ease of owning it, making anonymous calls, connecting to the internet. My mind wandered back through the handbag, pausing for a moment on the purse, imagining the coins and notes, each in their designated place, counted after each purchase. And a credit card, which may well give contactless payment which if I was careful, if I used it sparingly, would last for a few groceries. I toyed with the idea, ran possibilities around my head, considered the morality of perhaps taking just some of the money, thinking that need probably justified deed, and my need was certainly greater than hers; my poverty was lurking just around the corner, my next few meals were far from certain. Plus, I thought, I was already a thief, I couldn’t deny the label, there was no way to pretend that I was anything else. And I was no Robin Hood figure, the only person to benefit from my illegal acts was myself, there was no justification, therefore this tiny, almost offered-on-a-platter act, was just a tiny part of the whole, barely significant.

But then I pulled back my thoughts, reigned in the tantalising exploration of possibilities, and reminded myself of who I was, who I hoped to become. No, I might indeed be a thief, I might take those things I had no right to, but I wasn’t a petty criminal. I had not yet stooped low enough to steal from elderly ladies on trains. I would not let circumstance mould me into a creature I would loathe.

I turned back to the window, watching trees like hunchbacked old men guarding the road, and muddy fields full of pigs with slices of upturned barrels to sleep in, and roads that raced beside us before curling away into towns and villages and places we could never reach, glimpses of rivers and boats and occasional docks, all blurring into an indiscernible haze. I strained forwards, trying to see the roads, wondering which were the ones that we had driven along, a lifetime ago. But it was too hard to see them, they all looked the same. My eyes closed, and I slept.

Thanks for reading.

The book is available from Amazon, as a paperback or kindle book. I hope you will buy a copy to share with your friends.

*****

Please share.

anneethompson.com

*****