How can we know God? I believe he has given us several pointers: we see him in nature, we hear him in our conscience, and we find him in the Bible. God is bigger than we can imagine, he is truly good, completely dependable and he loves us enough to let us approach him, to ask for forgiveness and to show us the way to walk. We can trust God when all else lets us down.

When I was a child, I was taught that the Bible is God’s word. Fifty-odd years later, I would concur that this is true. But there is more to it than that.

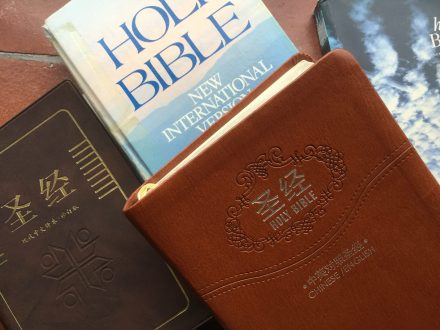

The books of the Bible were first written in Hebrew (Old Testament) and Greek (New Testament). When books are translated, someone has to make decisions about which words to choose. So how can we know whether what we read is what was intended to be said? We don’t have any original copies of the original New Testament, we only have fragments of documents (many found in ancient rubbish dumps in Egypt!) These fragmented copies of manuscripts are not identical, so how to choose which ones are closest to the originals? Do you take the ones we have most of, or the oldest ones?

Originally, Greek was written all in capital letters, with no spaces between words. ITMAYHAVELOOKEDSOMETHINGLIKETHISTOEARLYREADERSWITHANABUNDANCEOFPOSSIBILITIES. Scholars have taken the lines of writing and added spaces—but how do they know where to put them? (A BUN DANCE ON THE TABLE or ABUNDANCE ON THE TABLE?) Sometimes the context is obvious, but not always. Then the words are translated into English. Many have more than one meaning, so which one is the correct one to use? For example, “In the beginning was the . . .” The word used in the gap can mean ‘word’ or ‘reason’ or ‘message’ or ‘matter.’ Different Bible translations have made different choices. I personally favour ‘reason’ because “In the beginning was the reason” sounds very logical to me.

Our understanding has developed over time, as more of those fragmented manuscripts are found. For example, people used to think that the different Greek words for love meant different kinds of love, and when Jesus asks Peter three times whether he loves him, he uses different words to mean slightly different types of love. I have heard several sermons preached about just this, the vicar wanting to show that Peter was offering one kind of love to Jesus, and Jesus challenging him to love him more deeply.

They made good sermons—but scholars now know that this is incorrect, and the two words were simply different ways of saying the same thing, with no change of emphasis. The books were written in ‘everyday’ Greek, and as more and more examples of writing from that period are discovered, so our understanding of how words were used has developed.

Then there is the personality of the authors. Mark used the Greek equivalent of slang when he wrote his book. For example, when he writes about putting new wine into old wine skins, he uses the word ‘throws’ so it could read: “No-one chucks new wine into old wineskins!” but our Bibles have made this more formal: no-one puts new wine…

Does all this mean we should not trust the Bible? No! When we read the Bible, we discover the living God, we see the magnificence of his power, we learn that he is truly good, and ever loving. But the Bible is not equal to God—nothing is. The Bible can help to guide us as we try to walk the paths God has set for us, but we should be cautious never to use the Bible as a weapon. We cannot read the Bible and think we understand everything there is to know about God, that somehow God can be contained in the pages of a book. A humble walk with God does not allow us to take phrases and words and apply them as rules for other people.

I find this a sober lesson to learn. I had thought that by learning Greek and Hebrew, I would know for sure what the original authors had written. But I can’t, I can still only learn an uncertain version of what they wrote. We do not know exactly what every word, or every sentence originally meant. I can tell you that after looking at the ancient Greek version I think I might know the meaning of a phrase, but I need to be cautious.

Does this mean that God somehow failed to protect his special message to Christians? I remember as an assertive teenager, defending the accuracy of the Bible, saying that although it had been written centuries before, surely God, who can do all things, would protect the integrity of his special book. And yet, it is clear to my adult self that this is not the case. Even as I read the books in Greek, I cannot be sure I am reading exactly what was written. Christians do not believe that God dictated, word for word, our version of the Bible to the human writers (unlike some other religions, as I think Muslims and Jews do believe their holy books were dictated).

I wonder if perhaps, this was always the intention. God knows how people love to make rules, to be certain of how people should live (usually so they can apply it to other people). Did God, in his great wisdom, allow us only an uncertain view of his revelations, so that whilst the Bible would help us, it was only by looking to him that we truly learn? Is one of the biggest mistakes of the evangelical church today the tendency to hold the Bible as equal with God? Only God is God, and unless we constantly look to him, we will make all sorts of mistakes when understanding what the Bible says.

Perhaps we should not be pointing at words and phrases in the Bible and using them as ‘proof’ of doctrine. (How many times have I heard Jehovah Witnesses and Christians arguing about whether ‘The Word was God’ or ‘The Word was a god’? Are either party sure they should be so certain of their translation?) Is the gift of tongues a personal gift intended for all individuals today, or was it intended only for public use in the past? Does God only accept people after they have asked for forgiveness for their sins, or is anyone who comes to God, whatever their motivation, accepted because Jesus died for all? Were the church leaders who proved that the Bible sanctioned slavery wrong? Are the church leaders who prove that the Bible condemns homosexual relationships right?

We can all examine these issues, weigh them against our beliefs and form an opinion. But beware those who are certain that they always know the answer.

We can only humbly bow before God, and accept that he is God.