Several years ago, I read The Island, by Victoria Hislop. Although her writing isn’t really to my taste, I find her books interesting, and The Island described a leper colony, off the coast of Crete. I thought it would be interesting to visit.

We’re staying in Ierapetra, on the south coast (which is sunnier in October) so I shoved a jumper in my bag, and we headed North. It’s possible to catch a ferry from Plaka, which has free parking, so we drove there. The parking was free, the ferry cost €12 for a return ticket, which seemed reasonable, and the ferry ran every 45 minutes. We had just missed one, so we bought a ticket and then wandered up a pretty street while we waited. I needed a coffee and a washroom, so we bought some coffee (very good coffee) from The Pine Tree tavern. The washrooms were very clean (I think everywhere in Crete is very clean) and an espresso and an Americano both cost €2.50–which is as cheap as we have found.

The ferry arrived, we found seats, there was a short wait while it filled with passengers. The ride was very short. We came to a small harbour, with ferries from several other places. There was a ticket office. I don’t know why, but I had assumed the ferry included entrance to the island. Rookie error. It cost a further €20 each to go onto the island. I felt slightly cheated, which makes no sense because I would probably have paid €30 for a ticket on the mainland, but somehow the 2-stage payment felt like a trick. Next time I will do better research. A very vigilant woman was checking tickets at the entrance, and insisted on tearing them in half (even though I had wanted to keep mine—it cost me €20!)

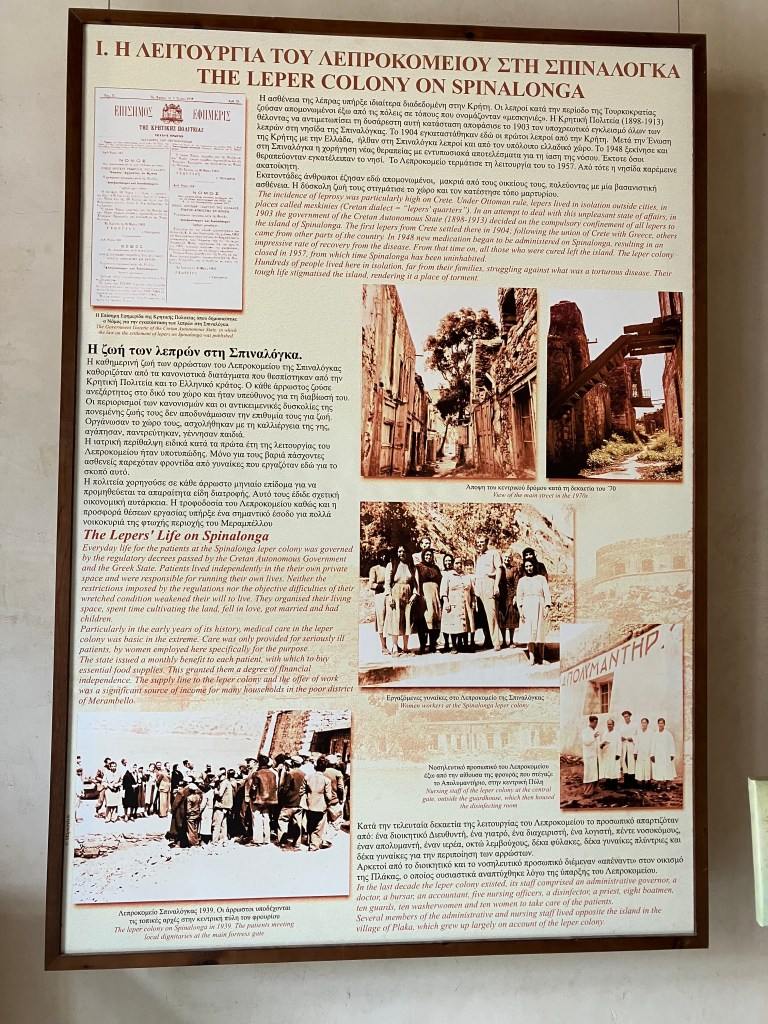

Spinalonga is a popular tourist destination, and it was busy. This didn’t especially spoil it—it was still just about possible to imagine the patients who were taken there in the early 1900s, who managed to survive until their illness defeated them. It was originally a fort, and they destroyed parts of the structure (to the horror of archeologists!) to build a settlement. I read that it became a community, and people even married and had children while living there. The novel I read was not, apparently, overly factual (I think it muddled some events, which happened in different times) but it’s fiction—it’s not meant to be a travel guide. I think Hislop describes places better than she describes people, and I recognised some of the buildings described in the book.

I cannot imagine how it would feel to live so close to the mainland, yet be unable to ever visit. If you were a strong swimmer, you could probably swim across, it’s not far. To be forced to live in isolation, to have to restart you life amongst strangers, must have been unbearably hard. As I read the signs (most were about the fort, but there were a few facts about the leper colony) I began to realise how strong those who made the island better must have been. Some of the people made a community, improving buildings, seeking to enforce a structure to life. As I wandered through their tiny houses, and looked at the uncompromising blue of the sea, I realised that there is a lesson for all of us. Life will always have tough, nasty, times. We choose whether we will fold into ourselves and wait to die, or pick up the pieces that are left and try to make something positive.

We caught the ferry back to Plaka and ended up at the wrong harbour! It was fine, as the town is very small, and we wandered along the main road and decided to find some lunch. We chose The Carob Tree because it had a table of old men drinking coffee and staring at the world, and I firmly believe that local old men know the best places to visit. We were not disappointed.

We chose a selection from the appetisers menu, with more coffee and a bottle of water. The Cretan Cheesecake turned out to be bread and carob bark, mushed into a sort of cake, with a local cheese and chopped tomatoes on top. It looked very pretty, tasted rather sour, and is definitely worth trying. My favourite was Graviera kantaifi, which was goat’s cheese baked in crispy shredded pastry, served with olive jam (which did not taste like olives—I don’t like olives). It was rich, and hot, and delicious.

We sat inside (near the old men) and watched the world drive past. At various points a van stopped outside, blocking the view, delivering fresh fish, or vegetables, or bottles of gas. It all felt very real and interesting.

I hope you have a good morning too. Thanks for reading.

Take care.

Love, Anne x