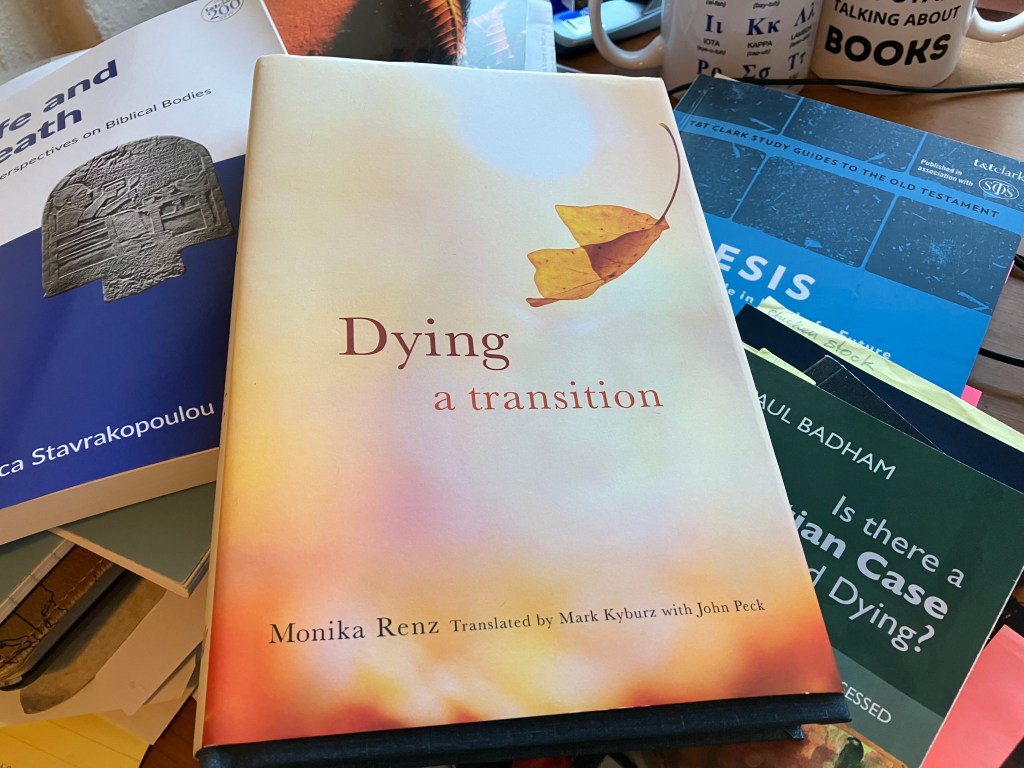

Book Review: Monika Renz, Dying, a Transition,

trans. Mark Kyburz, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015)

When I attended the debate on assisted dying at the medical school of Edinburgh University, one of the panel suggested that I should read this book. We were discussing the dying process, and whether dying is something that medics are trained to help with—and whether, in reality, it is a process where they should be involved. I felt that perhaps dying (as opposed to illness/recovery) is a stage of life best left to philosophers and theologians. I am not sure that medics understand dying, or that it is particularly relevant to their role as healers. Dying, I argued, is something that happens after the role of the medic has ended.

The book is thought-provoking, and I recommend you read it for yourself. You might not agree with everything written (nor should you ever expect to agree with everything that anyone writes). But it might challenge you, and help you to formulate your own ideas about dying. Most people that I speak to dislike thinking about dying—they find it an uncomfortable topic except in the abstract, when it applies to ‘other’ people. When I was about to have surgery to remove a brain tumour, I found this extremely unhelpful. I needed to confront the possibility of dying. None of us can escape the dying process—first with those who we love, and eventually our own death. I think reading Renz’s book will help you with both. I found it tremendously reassuring.

Renz writes for professionals dealing with palliative care, so her style is academic, but I don’t think you need a degree to understand the book. (You can always skip over some of the more academic pages.) Renz works with cancer patients in Switzerland, and her initial study was with 600 patients (which isn’t a huge range, but is big enough to give an indication of general trends). She analysed her data, and compared it to other studies, then refined her conclusions. The book therefore represents the conclusion of several years of work.

The patients studied were all dying. Some were religious (various religions) others were not (and some were ‘devout’ atheists). Renz found that the dying process for all of them was similar, and went through the same phases—though the amount of time spent in each phase varied. She offers advice as to how each phase can be eased by practitioners and family members—which I assume will be helpful when you next are close to someone who is dying.

To summarise the whole book (and really, you should read it yourself) Renz views dying as a transition, with marked phases. She talks about people going through a final stage, which she names ‘transition’ when they lose all sense of ego. By ‘ego’ she doesn’t really mean pride, though that is a part of it—more that the patient loses all sense of self. Just as a young baby has no pride or shame—pooping is something that happens but the baby is not embarrassed, they don’t care if they dribble or make noises. As a person nears death they too go through a similar phase, which Renz says can be distressing for relatives—who do have a sense of ego and therefore feel embarrassed to see their loved one in a position they see as ‘shameful’. But it’s not shameful, it’s just a body behaving how bodies behave without an awareness of social conventions. Renz states that the patient is not embarrassed, they feel no shame because they have ‘transitioned’ to a state where their body is no longer important.

Part of this transition is also a letting-go of earthly things. She says that for some people this is difficult, they do not want to leave pets or family or a role—and this is a necessary struggle, that changes them into a state whereby they are ready to die. Renz understands the process to be formative, even if difficult. She also describes an ‘encounter’ with a spiritual world—even for people who are not religious or are staunch atheists. Sometimes this is a period of fear, and she suggests actions that can calm the patient, helping them to find peace. She describes patients ‘seeing’ their deceased ancestors, or spiritual beings who are waiting for them to die, and how this is often comforting to the patient (even if perturbing for the relatives).

I found it interesting that there seemed to be the same phases of dying for both the religious and the non-religious person. I have never been present when a person died, so I cannot evaluate the truth of what she says, but I did find it comforting. Renz views dying as a natural process, a natural part of life, and one that should be recognised and not feared. Even when a death is a struggle, Renz equates this to a difficult birth—where there is sometimes pain or fear, but it is a process that leads somewhere. She suggests that we should not shy away from difficult deaths, or seek to shorten them or dull the senses, because the struggle is part of the preparation for what comes next.

I’m not sure how Renz’s research shapes the debate on assisted dying, and she was a little fuzzy on instant death (like an accident or a murder). She simply thought the phases happened instantaneously—but obviously this is not something she could test. Therefore some of the ‘research’ was speculation, but I didn’t feel that detracted from her overall findings.

As I said, I recommend you read the book. I found it very reassuring, it took away the fear of death. Renz shows that death is as natural as birth. It may be beyond our control, but it does not need to be feared. (Though I would note that the death of other people is always, in my experience, completely horrible. But perhaps it helps if we can view the stages as both necessary and natural. I don’t know.)

I hope you have a good day, and that death doesn’t trouble you. Thank you for reading.

Take care.

Love, Anne x