27/1/2025

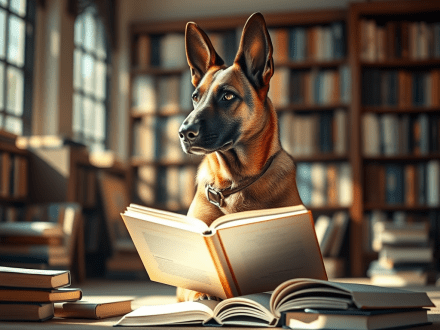

We went to New York (this is January, before the tariffs), Meg went to kennels. She was happy enough to walk in, and greeted the staff like long-lost relatives, so I don’t feel guilty leaving her there. They take her for a walk each day, and she walks around the woods carrying logs (though she’s on a lead, so no chasing sticks).

However, when we collected her this time, they said she is aggressive towards other dogs, and lurches towards them when walking—though is fine when next to them in the kennel. This is a bit like when we drive—every dog we pass Meg barks at (it doesn’t make for peaceful journeys). I’m not sure what to do about it really, as she is fine when she’s with me in the woods.

Actually, she is brilliant in the woods. I forgot to take the lead yesterday, and I didn’t need it. I held a stick when I opened the boot, and Meg waited next to the car, watching to see where I would direct her. Other dog-owners were returning to the car park, and cars were whizzing along the main road, but Meg ignored them all. We had a lovely walk through the woods, I threw sticks, and called her when she got too far away, and she was completely obedient. We passed several other dogs, crossing paths with them, but whether they barked at her or not, Meg completely ignored them. Great. At the end of the walk I called her to heel, and we returned to the car (still no lead). I opened the boot, told Meg to jump in, and …nothing.

This has become a feature. When we return to the car, whether after a quick trip to the supermarket or a long walk round the woods, Meg refuses to get back into the car. She stands there, and looks at me. In her favour, she does not chase other cars or dogs, she just stands there, quietly waiting for me to take her for a longer walk. And I stand there, quietly waiting for her to jump into the car. Sometimes we stand there for a full 5 minutes, staring at each other, fully understanding what is being expected, refusing to give in. I usually break first, and practically choke her by trying to haul her into the boot. At which point she jumps nimbly in, giving me a withering ‘you have no patience’ look. Which is correct, I do not.

I’m not sure whether this counts as obedient or bad. She knows what I want, and doesn’t run away—but nor does she obey and get into the car. When I’m in a rush, it’s infuriating. I have started keeping dried fish treats in the car, as a bribe. The only change is that my car now stinks for fish, Meg still won’t get in.

14/2/2025

Meg has been fun this week. She is now fairly reliable when left alone in a room, and usually settles down near a radiator and snoozes. Only fairly reliable, as she did empty a plant all over the kitchen floor—so I wouldn’t leave her alone for too long, but gradually I am trusting her more.

I still cannot let her interact with my other animals though. I doubt she would hurt them on purpose, but she would definitely chase them, and might bounce them, which would be the equivalent to a truck landing on your head. When I’m sorting out the poultry, Meg rushes around, barking and trying to chase them through the side of the fence, which they find very upsetting. I realise I ought to spend time training her –taking her to the coop several times a day, and training her to sit or fetch her ball, thus teaching her to ignore the birds. But life is too busy, and it’s easier for now to just leave her in the kitchen whenever I need to be with the birds. Not ideal, but it works for now.

My other failure is chasing cars in the lane next to the garden. Whenever a car goes up the farm track, Meg charges at full speed along the fence line, trying to keep up with it. It’s good exercise I suppose, but it’s also reinforcing the drive to chase cars, which I really want to break her of—but I cannot be in the garden with her all the time, and there is no other way to stop her. I am telling myself (fully aware that I am probably lying to myself) that she can chase cars in the garden but can learn not to chase cars in other situations. I think this is untrue, but other solutions seem too difficult at this point. Maybe she will grow out of it.

When I return from my morning run, I usually spend some time training Meg. This is very simple—I lie on the lounge floor (where she is not allowed) doing my exercises, and Meg sits in the doorway. I have a ball, which she is not allowed to touch, and every few minutes I throw it, she retrieves it, I take it from her, put it on the floor and tell her to ‘leave!’ and then we start the whole exercise again. Today, Husband was working in the study, and I wasn’t sure throwing the ball up and down the hall would be quiet enough, so I decided to do my exercises on the landing carpet. Disaster! We went upstairs, Meg sat on the mat next to the radiator (her favourite place) I lay down on the floor and whump! A very happy German Shepherd dog landed on top of me! She was so excited, bouncing on me and licking my face, her tail smashing into anything in range as it swung backwards and forwards like a mad propeller. I couldn’t get her off me for ages, she is so strong, and was so excited that I was joining her on the carpet. I’m not quite sure what game she thought we were playing, but it clearly made her very happy. By the time I managed to stagger to my feet, I decided the wrestling match had been more than enough exercise for one day, so I went for a shower.

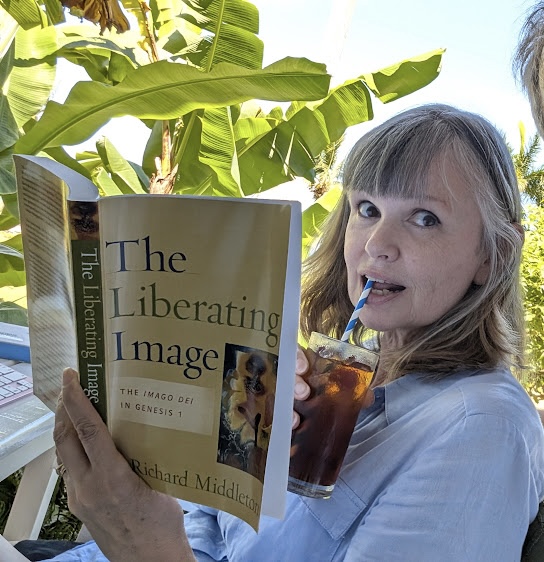

One afternoon this week, I was very tired but wanted to listen to an online lecture. So I took my phone to bed, and nestled into the pillows, ready for a sleepy listen. Meg followed me into the bedroom (where she is not allowed, but this happens more often than I like to admit) and lay down on the mat. She must have been tired too, because she started to snore. Then the lecture started, and I turned up the volume on my phone. Meg stopped snoring, and groaned. I ignored her. She groaned again. I ignored her. Then her head appeared alongside mine on the bed, and she stared at me, very pointedly, and groaned again. Clearly she was not appreciating the lecture on apologetics. She had a look in her eye that told me that if the noise didn’t stop, she might jump up onto the bed. Not to be encouraged. I took her downstairs, and listened to the lecture in a different room.

Usually when I work, Meg is very good. She lies on the carpet behind me, snoring and farting, with the occasional groan if I work for too long. It’s good (if smelly) company.

I hope you have some good (not smelly) company this week. Thanks for reading.

Take care.

Love, Anne x

*****

anneethompson.com

*****