Was Moses an Historical Person?

Or was he invented to prove a point?

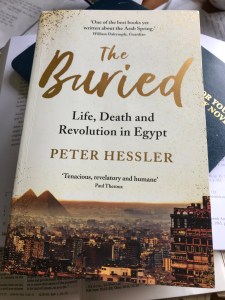

Sometimes, things seem to make a ‘perfect storm’ don’t they? Lots of unrelated things all come together and provoke an unexpected reaction. This happened recently with the story of the Exodus. I was reading a book by Peter Hessler, an author I enjoyed when I started to learn Mandarin, as he lived in China for a while. He has now written a book about living in Egypt, learning to speak Arabic, and discovering the Egyptian culture. I ordered a copy and started to read. At the same time, I just happened to be reading the book of Exodus in my daily Bible study time, and of course, this is all linked to Egypt. At the same time, the sermons we were watching from Cornerstone Christian Church in NJ (where we used to live) were all about…the Exodus from Egypt! My head was full of all things Egyptian.

Sometimes, things seem to make a ‘perfect storm’ don’t they? Lots of unrelated things all come together and provoke an unexpected reaction. This happened recently with the story of the Exodus. I was reading a book by Peter Hessler, an author I enjoyed when I started to learn Mandarin, as he lived in China for a while. He has now written a book about living in Egypt, learning to speak Arabic, and discovering the Egyptian culture. I ordered a copy and started to read. At the same time, I just happened to be reading the book of Exodus in my daily Bible study time, and of course, this is all linked to Egypt. At the same time, the sermons we were watching from Cornerstone Christian Church in NJ (where we used to live) were all about…the Exodus from Egypt! My head was full of all things Egyptian.

I decided I wanted to write a story, through the eyes of Moses’ wife, about Moses the man. Who was he, this misfit who led a rebellion, the go-between for God and his people, the Egyptian-Hebrew hybrid? What kind of person can watch his adopted family suffer plagues—even the death of his nephew—and remain unmoved? Who is able to stand up to rejection from his blood-relatives, and not fear the might of his adopted-family, and can remain true to his God throughout it all? And what would it be like to be married to this man, this single-minded leader of the people?

But before I could write a story, I needed to do some research. What were the customs and life-style of people 3,000 years ago? What did they wear, eat, believe in? I asked people to recommend books, and I started to read. I have now spent several weeks reading, I am still not ready to write my story, but have learned a lot of ‘facts’ and theories about Moses and the time he lived in. I thought I would share my most interesting discoveries with you, because some of them were surprising.

One of the first things I discovered was that there is very little historical evidence from this time—almost no secular data to back-up the Bible account. Something (no one knows what) happened at the end of the Bronze Age, something that destroyed all the complex major cities, and most of the evidence about the lives of the people, so there is almost no evidence to support the account of the Old Testament. For this reason, many scholars believe the account is not factual—they think there never was a nation of slaves, freed through plagues, led away by a man called Moses, to a promised land that was unified under Kings David and Solomon—they say it is all legend and myth, written to explain relationships and understand God, but not historical fact. Could this be true? I watched a very convincing YouTube video, which was based on the book: The Bible Unearthed by Finkelstein and Silberman, and it was absolutely certain that the Old Testament is unverifiable myth and legend.

Undeterred, I kept looking. I wanted to read what the scholars who don’t believe in the authenticity of the Bible had to say (“the wise man learns more from the fool than the fool does from the wise man” and all that!) so I read a whole plethora of books (including The Bible Unearthed by Finkelstein and Silberman). Here’s what I learnt:

Sigmund Freud said that after various studies, he thought Moses was an historical figure, living about thirteenth century BC. However, he took task with his name, saying that although the Jews name him “Mosche” it’s more likely that an Egyptian princess would give him an Egyptian name. Freud refutes that “Mosche” (the Hebrew version of Moses) means “He was drawn out of the water” as per the Biblical account, saying at best it means: the drawer out. (I felt he was splitting hairs here!) He concludes that Moses was probably named Mose, which is an Egyptian word meaning ‘child.’ It was common to use this at the end of Egyptian names, and we know of the Pharaohs Ahmose and Ptahmose and Thutmose, for example. Apparently, the final ‘s’ of ‘Moses’ was added when the Old testament was translated from Hebrew to Greek (so I presume that the Jewish Torah has the original Mosche or Mose). Freud then went on to compare the basket the baby Moses was placed in with the womb, and the River Nile with the mother’s birthing waters, so he lost me at that point.

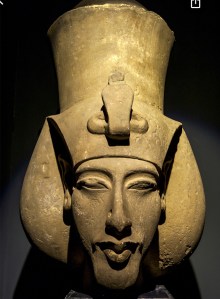

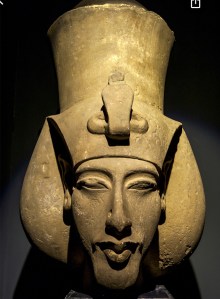

Akhenaten

c1346 BC

Freud is certain that Moses was Egyptian, and this is how he ‘got the idea’ for a new, monotheistic religion (a religion that says there is only one god). Freud says this idea came from Amenhotop IV, who enforced the worship of a single god: Aten. Freud’s argument is that IF Moses was Egyptian, then his mother would be Queen Hatsepsut (sometimes spelt Hatshepsut), and Thutmose I would be his grandfather. This would make him a rival to the throne of Amenhotep II, as the Pharaoh would be Moses’ nephew. This, says Freud, explains why Moses spoke with such authority, and why the Pharaoh didn’t simply kill him when he started to be annoying. (I hope you’re keeping up with all these names. Very annoying when parents name their children after their relatives!) Hatsepsut was a powerful woman, married to her brother Thutmose II, she is thought to have reigned jointly with Thutmose III for a while, though he is known to have later tried to destroy everything with her name on, erasing her from history.

However, if Moses ‘copied’ the idea of one god from Amenhotep IV (who changed his name to Akhenaton) then the Exodus would have to be after this. The Akhenaton period is 1353 – 1336 BC. I had never heard of Akhenaton, though I had heard of his beautiful wife Nefertiti, and his son (by a different wife) Tutankhamum.

Going back to the name of Mose, this also ties in with the lecture I attended last year at the British Museum. They suggested that Thutmose III was the pharaoh of the plagues. ( Blog link here. ) Like Freud, they also thought Thutmose I, with his powerful powerful daughter, was the Pharaoh during the time Moses was born and it would make sense for her to be the princess who found Moses, and then gave him a name linked to her father (Thut-mose). This would date the Exodus to around 1446 BC.

We know that Thutmose III disappeared mid-reign, and that the next Pharaoh was not his first son (which fits in with all the first-born being killed in the final plague).

Thutmose III

Who was probably the Pharaoh during the Exodus, when all the Israelites left Egypt.

In Exodus (the book) it appears to name a Pharaoh—Raamses—but this is apparently more likely to be referring to a place. The Old Testament often ‘muddles’ people and place names, and one ‘proof’ that it was written much later than the history it is meant to be describing, is that some of the places named did not exist until centuries later.

However, if the books were edited centuries later (but written when they said they were) then it would not be beyond belief that those later scribes added the names of places they knew, to tell their readers where the events took place. For example, if I was editing a book about a journey in 200BC from my house to where London now is, I might add that they walked from here “to London” even though London, as a place, did not exist until 43AD (this would then be ‘audited’ by my family who would insist I changed such an illogical statement, but there is lots in the Bible that tells me those early writers did not suffer living with auditors like I do, and many of their ‘facts’ are a little imprecise!)

Another piece of evidence in the British Museum is the city of Jericho, which the Bible says was destroyed when the Israelite army marched around it. When archaeologists examined the ‘dead zone’ (the layer showing when the walls were destroyed) they found that not the entire wall was destroyed. This supports the Biblical story of a prostitute, Rahab, surviving the destruction—her house was in the wall of the city. The ‘dead zone’ has the remains of pots, which still had grain in because the people didn’t eat the grain and the invading army did not take the grain as plunder (which was unusual). Archaeologists have also found ancient tombs, which were Egyptian-style in design, but this changed about the time the Israelites would have arrived. The archaeological evidence shows a gradual decrease in Egyptian influence in the whole area, which again ties in with when the Israelites would have arrived back in Canaan.

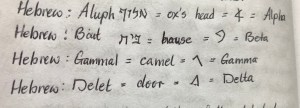

I read Who Were the Phoenicians? by Nissim R. Ganor. The book was originally written in Hebrew, and I was reading an English translation, so it was quite heavy-going in places (actually, scrap that, it was very heavy-going! It took 195 pages before he had finished ‘proving’ who the Phoenicians were not). Ganor was exploring the Phoenicians, the people who first devised an alphabet (before this, people wrote either Egyptian hieroglyphics, or Chinese script or Mesopotamian cuneiform). It is from the Phoenicians we get our word ‘phonics,’ the idea that symbols can represent sounds.

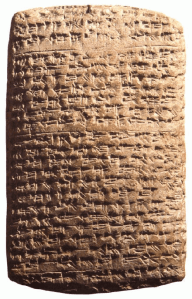

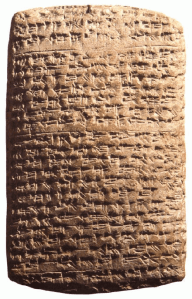

Tell el-Amarna letters.

They describe the ‘Habiru’ (Hebrews?) attacking cities, and the letters ask Egypt for help.

Ganor refers often to the Tell el-Amarna, which are clay tablets found in Upper Egypt. They were engraved about 1360BC, and were diplomatic correspondence between Egypt and Canaan, written in Akkadian cuneiform (cuneiform just means wedge-shaped carvings). Some of this correspondence talks about invasions of cities by an unstoppable tribe that is taking over the area. They describe kings being killed and buried at the city gate—all of which ties in with the stories of Joshua leading the Israelites into battle. The Tell el-Amarna is perhaps a tiny piece of related evidence, but it is still evidence that supports the Bible view. I don’t think ‘lack of evidence’ necessarily disproves something, and if the only evidence available supports an accepted view, then why try to ‘disprove’ it? The Amarna letters refer to invaders named Habiru, which was very likely to be the Hebrews.

Ganor also states that until recently, people believed that history was only recorded orally until 10BC (which makes it less reliable). However, new engravings have been found that show people had phonetic writing in 1500BC, and therefore it is entirely possible that Moses did write an historical account of the Exodus, as claimed by the Bible. (If you look online, you can read the diaries of Petrie, who was an archaeologist who found evidence of alphabetical writing—in a very unrefined form—from 1500BC, during his 1905 excavations.)

Knowing when the Exodus took place is another problem, even for scholars who believe it happened. The Old Testament says the Israelite slaves lived in Goshen. If this was in the Nile Delta, then the Exodus cannot have been before 1200BC (the period of Raamses II) because there was no substantial building around that time in that area (and they can’t have commuted very far to work!) However, much of the evidence for this is flimsy, an attempt to fit the facts to the Bible account. Some scholars have therefore said the Exodus never took place, others say that actually there were TWO exodus, one during the reign of Raamses, when half the Hebrews left, and another one later—this is because the evidence on the Tell el-Amarna doesn’t fit with the timing of the slaves leaving during the reign of Ramses.

It seems more likely that Goshen was situated in the area of Heliopolis (the ancient city of On) which is now modern-day Cairo. From there, it is three days journey to Yam Suph (Red Sea) and according to Hutchinson (The Exode, 1887) this route from Egypt across the Arabian Desert was probably the route of the Exodus (he bases this on Bedouin tradition, not the Bible—but it fits!) The ancient city of On (modern day Cairo) has several remains from Thutmose III and also Raamses II, though the remains credited to Raamses are always suspect as he would remove other Pharaoh’s symbols and add his own, to gain credit for things others had made.

In Who Were The Phoenicians? Ganor explains in great detail about how the timing of the Exodus with Ramses is erroneous (trust me, a LOT of detail!) Ganor says that it simply cannot have happened then, and shows all the reasons why it must have happened earlier, and all the evidence that supports this. I was convinced. He ‘proves’ the Exodus was about 1446 BC. This then discounts Freud’s clever theory about monotheism starting with Akhenaton (who came later).

In fact, it seems to me more likely to be the other way round. Akhenaton would have heard the stories of the plagues, and known that all the Hebrew slaves had escaped from Egypt, and he probably decided that worshipping the same God as the Hebrews was a good idea. This would also explain why in the el-Amarna it states that he refused to help the Canaanite kings in their wars with the Hebrews. However, as the Hebrews worshipped several gods during their time in Egypt, Akhenaton wouldn’t have known which deity to worship, hence the decision to worship Aten.

I then read The Bible Unearthed* by Finkelstein and Silberman, which is the book that the very convincing YouTube video was based on (the one which says none of the Old Testament is historically factual, and it is all myth and legend). The authors spend a long time discounting the story of the Exodus because it cannot have happened during the time of Raamses. I felt so frustrated with them, and wanted to tell them to read Who Were The Phoenicians? and then start again! All their arguments were based on the Hebrews leaving Egypt during the time of Raamses, and they went into great detail as to how this was impossible archaeologically, and therefore impossible per se. They even talk about the cities mentioned in the Biblical account—the ones conquered by the Israelites when they reached Canaan, saying that although they existed centuries before Ramses, and were rebuilt and powerful again centuries after Ramses, they did not exist at that time, therefore the Exodus never happened because etc etc etc. I wanted to shout at them, and tell them to rethink their basic premise, and that yes, the cities existed before the time of Ramses because that is when the Hebrews left Egypt.

They also discuss a document, written by an Egyptian historian Manetho in the third century BC. He tells the story of the Hyksos, who invaded Egypt and founded a dynasty and who were driven out by a strong Pharaoh. Later archaeologists have found that the Hyksos were from Canaan, and there is a gradual spread of Canaan influence in Egypt, which stopped around the time of Pharaoh Ahmose. Again, if you take the view of both the British Museum, and Ganor, then this ties in with the timing for Ahmose being the Pharaoh who began to oppress the Hebrews. So the evidence used to disprove the Exodus as an historical event yet again supports it.

My understanding of how archaeology works is that someone discovers something, and based on previously known evidence, they make conclusions about it. These conclusions then effect further findings. If those conclusions are proven to be wrong, then they should be adjusted, or the way they effect future findings will continue to be wrong. A simple illustration of this point would be:

Someone unearthed all the possessions of Henry, and they included a stamp collection. Based on previous knowledge, they said that eldest sons are usually named after their father, and as Henry is the eldest son, his father must also be named Henry. They also concluded that Henry had decided to collect stamps. Later, the possessions of another son, Charlie, are also unearthed. Charlie also collected stamps, so they conclude that Charlie copied his elder brother and decided to collect stamps. Perfectly reasonable assumption. But then, they unearth Charlie’s birth certificate. Charlie is an adopted son, and he was older than Henry. The conclusion must now be adjusted: It was Henry who copied Charlie when deciding to collect stamps, because Charlie came first.

The conclusions drawn in The Bible Unearthed are based on misinformation. They have placed the Exodus too late in history, and then concluded that the Israelites never formed a large empire, the Kings David and Solomon are mythical figures, their religion was a copied mish-mash from another race—the Phoenicians. Someone has used these wrong conclusions to make a convincing YouTube video, and people are listening to the well-presented information and assuming it is correct. But it is not. Beware listening to the clever voice that shouts loudest. It might be wrong.

There is more evidence for the Israelites reaching Canaan and conquering cities. The Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus (about 30BC) wrote a history of the area. He describes the Exodus from Egypt in detail, and how the Israelites defeated other nations and destroyed their cities. He doesn’t ever use the term ‘Hebrew’ or ‘Israelite’ but rather calls them ‘Phoenicians.’ You will recognise this name from Ganor’s book: Who Were The Phoenicians?

Ganor also believes the Hebrew slaves became the Israelite nation, and the Greek name for them was the Phoenicians. (He took 195 pages of proof to reach this conclusion! It was not an easy read but we got there eventually.) He also quotes Herodotus, another Greek scholar, who wrote about the three nations from Persia to Egypt: The Syrian Palestinians (who Ganor believes were the Philistines in the Bible) the Phoenicians and the Arabians. Herodotus himself links the Phoenicians with the Israelites; he also says they originally came from the ‘Red Sea’ which from his other writings can be deduced to mean ‘from Egypt.’

Greek writers also describe there later being two types of Phoenicians, those who circumcise and those who don’t—which ties in with the Bible account of the Israelite nation splitting, and the southern kingdom (Judah) remaining true to God and the laws given during the Exodus, and the northern kingdom, which pretty much ignored God, and had lots of different gods and were eventually taken away by the Babylonians.

The book goes on to talk about how the alphabet was formed—which Ganor also thinks started with Moses, but although this was hugely interesting, it doesn’t form part of the argument that Moses existed as an historical figure, so I will leave that for a later blog.

Now, although Ganor has pretty much ‘proved’ that the Hebrew slaves left Egypt in a mass exodus, and crossed the wilderness, and then conquered cities in Canaan and occupied them, all as per the Old Testament, he does not believe in the God part. Ganor believes that Moses wanted to establish a new religion, and therefore came up with the idea of one God. Some of his evidence makes sense. For example, we know from reading the Bible that people worshipped more than one god, because they are frequently told to stop! When Moses kills half the Israelites because they are worshipping the golden calf, he accuses them of ‘returning to the gods of Egypt’ and indeed, until Moses emerges from the mountain with the ten commandments, the people have not been told they should only worship one God.

Ganor, who is a linguistic historian, uses the names of God in the Old Testament as evidence. He says that the frequent mention of planting trees by Abraham and Jacob show that they worshipped trees. Jacob is thought to have worshipped the Asher tree, and the Hebrew word for ‘God’ is ‘El’ hence his name was changed to ‘Asher-El’ which became ‘Isra-El’ or Israel. Later, the Hebrews are known as “sons of Asher El” or “sons of Israel.” Ganor also says that the name ‘Adon’ is from an Egyptian god, and gradually became the basis for the Hebrew word ‘Adonai’. When, after settling in Canaan, the Israelites began to worship a myriad of gods, the god Adon became henotheistic (which means he was sort of the ‘king of gods’—all the other gods worshipped him). The prophets kept trying to re-establish a monotheistic (one God) religion.

There is an interesting link with the Greek god Eshmun sar Kadesh, which was a snake god used in medicine. Artefacts show that the Greeks acquired this god from the Phoenicians. The symbol is still used today in some places, of a snake wrapped around a pole (you see them outside pharmacists). Now, what has a snake got to do with medicine? Well, in the Bible account of the Exodus, when the people were leaving Kadesh (Numbers chapter 33) they were being bitten by snakes, and Moses made a bronze snake on a pole and held it up. When the people looked at it, they were saved from the snake bites and lived. After the Exodus, some of them were continuing to worship this bronze snake, saying it was a god of medicine (it’s like these people were continually looking for new gods to worship!) The Bible doesn’t hide that this was happening, and in 2 Kings chapter 18, there’s the story of a king finally destroying the bronze snake so people would stop worshipping it.

There is an interesting link with the Greek god Eshmun sar Kadesh, which was a snake god used in medicine. Artefacts show that the Greeks acquired this god from the Phoenicians. The symbol is still used today in some places, of a snake wrapped around a pole (you see them outside pharmacists). Now, what has a snake got to do with medicine? Well, in the Bible account of the Exodus, when the people were leaving Kadesh (Numbers chapter 33) they were being bitten by snakes, and Moses made a bronze snake on a pole and held it up. When the people looked at it, they were saved from the snake bites and lived. After the Exodus, some of them were continuing to worship this bronze snake, saying it was a god of medicine (it’s like these people were continually looking for new gods to worship!) The Bible doesn’t hide that this was happening, and in 2 Kings chapter 18, there’s the story of a king finally destroying the bronze snake so people would stop worshipping it.

Looking at the Bible, it too makes it clear that the Israelites worshipped lots of gods (though to be honest, I had missed that when I read it—it’s not something that Sunday School teachers tended to point out!) I don’t know what I think about the idea that Abraham and Jacob worshipped tree gods, but there are references to Jacob being told to destroy idols, and he does bury them under a tree, so it might be significant. But the Bible also makes it clear that there is also one true God, and he is God.

My thoughts are that by denying the existence of God, Ganor rather misses the point. He can explain when the Exodus took place, and has provided evidence to support the Old Testament books, but he never addresses how they escaped. Why would Pharaoh let them go? If there is no God, there can not have been the plagues, and so the very fact of how they escaped is never solved. Ganor seems to go to an awful lot of bother to prove that God is created by Moses and perpetuated by the leaders who followed him—it would be more logical to simply acknowledge that God exists.

One fact that interested me was the name God gives when he meets Moses at the burning bush. Moses asks: ‘Who shall I say you are if they ask?’ (which is another proof that the Hebrews had several gods) and God says: “Ehye Asher Ehye” which apparently is ancient Hebrew for: “I will be whoever I will be.” Most Bibles translate this into the English: “I am who I am,” but I think the original translation says something slightly different, and I find that intriguing.

The name of the book of Exodus is also a Greek addition. It was originally called: “These are the names,” in Hebrew, according to David Pawson. I had never heard of David Pawson, he seems to be a Royal Air Force chaplain, who wrote a very fat (and very interesting!) book. It’s worth reading if you are interested in a few factoids around the books of the Bible. I was lent a copy, and liked it so much I ordered one for myself, even though I completely disagree with some of what he writes, mostly it is hugely interesting. One observation he makes is that according to the Bible, the Hebrew slaves were told to make bricks without straw, which would make them very heavy. He says, Archaeologists have found buildings built with bricks made with straw at the bottom, then a layer of bricks made with rubbish (while people scrabbled around trying to find a substitute) and then bricks made with just clay.

Going back to the Phoenicians, there is evidence that they were a trading nation, travelling to Crete and Greece and beyond. Different historians remark on the Hebrew influence in some Greek names and words. It is thought that the Phoenicians reached the peak of their trading empire about 1000BC—which is when the Bible says King Solomon reigned over a strong trading nation.

I don’t know what you believe, and there seems to be no way to prove anything, but personally I choose to believe the Bible account is historically accurate. It is true, the evidence is flimsy, and often circumstantial, but that doesn’t mean we should ignore it. I think it takes a sort of ‘faith’ to say the books in the Old Testament are not at all historically factual, written by authors centuries afterwards to justify invading the northern kingdoms of Israel. I prefer personally to have ‘faith’ that the Biblical records which claim to be history (some of them are poems or stories, and don’t claim to be otherwise) are factual. We lose some understanding because we don’t read them in ancient Hebrew, but I choose to believe the events actually happened.

***

The whole idea of language and translation and lost meanings is something that worries me. The Bible was not written in English! When archaeologists found the Dead Sea Scrolls, they found a copy of the Old Testament scriptures that predated other copies by about a thousand years. They found four differences, which I believe were the way some names were spelt (so nothing, really). The early scribes were incredibly careful when they copied scripture, they even counted letters, to ensure the correct letter of the entire manuscript was in the centre. For centuries, the Old Testament books were passed from generation to generation, unchanged. But then the New Testament was written, and the scriptures were translated into Greek. Instantly, there would be changes, but both the Greek and Latin versions of the Bible were pretty well standardised. The Bible continued unchanged—until now. Now we seem to have a new version every week! We have the Hip-Hop Bible, and the Youth Bible, the Good News Bible and the English Standard Version Bible. Each one is slightly different, even the ones which are translations from the original Hebrew and Greek.

When I read books like Who Were The Phoenicians it makes me realise how much emphasis we place on certain words and phrases, and how these are changing as new translations appear. In evangelical churches, it sometimes seems that the Bible and God are held in equal authority, and yet the Bible, as we read it, is based on the decisions and understanding of the person who translated it. Should we therefore be taking snippets and deciding whole doctrines? Should individual words and phrases be given great weight when we make our rules and set our beliefs? I believe that God is bigger than the Bible, and that we should take great care when we quote the Bible as ‘evidence’ for what God wants.

The Bible is given so that we can understand God better, it shows us something of his nature, but we will never completely understand God. We are not meant to. Should translations of the Bible be given the importance that they currently are? I wonder whether they should be viewed as a resource, but we should constantly remember that they are only translations. My understanding is that the Jewish religion insists that all children learn some Hebrew, and they read the Torah in Hebrew at their ‘coming of age’ service. I think that the Quran can only be read in the original Arabic because the phrases fit together like a pattern. It seems only Christians are comfortable with most of their teachers only ever reading the Bible in translation. I wonder if they are right.

Books:

The Bible Unearthed by Finkelstein and Silberman

Who Were The Phoenicians? by Nissim R. Ganor

Moses and Monotheism by Sigmund Freud

Unlocking the Bible by David Pawson

The Buried by Peter Hessler

You can listen to Fred’s lectures here: https://subsplash.com/cornerstonechristianchur/media/mi/+ft3y8mb

(I usually skip through all the news and songs and just listen to the talk! You want the early August 2020 talks)

Tomorrow, I’ll look at whether it’s likely that Moses invented phonetic writing and the alphabet. (It will be a shorter blog, I promise!)

Thanks for reading. (You deserve a coffee after all that!)

Take care.

Love, Anne x

Thank you for reading

anneethompson.com

Why not sign up to follow my blog?

Look on your device for this icon (it’s probably right at the bottom of the screen if you scroll down). Follow the link to follow my blog!

*****

Sometimes, things seem to make a ‘perfect storm’ don’t they? Lots of unrelated things all come together and provoke an unexpected reaction. This happened recently with the story of the Exodus. I was reading a book by Peter Hessler, an author I enjoyed when I started to learn Mandarin, as he lived in China for a while. He has now written a book about living in Egypt, learning to speak Arabic, and discovering the Egyptian culture. I ordered a copy and started to read. At the same time, I just happened to be reading the book of Exodus in my daily Bible study time, and of course, this is all linked to Egypt. At the same time, the sermons we were watching from Cornerstone Christian Church in NJ (where we used to live) were all about…the Exodus from Egypt! My head was full of all things Egyptian.

Sometimes, things seem to make a ‘perfect storm’ don’t they? Lots of unrelated things all come together and provoke an unexpected reaction. This happened recently with the story of the Exodus. I was reading a book by Peter Hessler, an author I enjoyed when I started to learn Mandarin, as he lived in China for a while. He has now written a book about living in Egypt, learning to speak Arabic, and discovering the Egyptian culture. I ordered a copy and started to read. At the same time, I just happened to be reading the book of Exodus in my daily Bible study time, and of course, this is all linked to Egypt. At the same time, the sermons we were watching from Cornerstone Christian Church in NJ (where we used to live) were all about…the Exodus from Egypt! My head was full of all things Egyptian.

There is an interesting link with the Greek god Eshmun sar Kadesh, which was a snake god used in medicine. Artefacts show that the Greeks acquired this god from the Phoenicians. The symbol is still used today in some places, of a snake wrapped around a pole (you see them outside pharmacists). Now, what has a snake got to do with medicine? Well, in the Bible account of the Exodus, when the people were leaving Kadesh (Numbers chapter 33) they were being bitten by snakes, and Moses made a bronze snake on a pole and held it up. When the people looked at it, they were saved from the snake bites and lived. After the Exodus, some of them were continuing to worship this bronze snake, saying it was a god of medicine (it’s like these people were continually looking for new gods to worship!) The Bible doesn’t hide that this was happening, and in 2 Kings chapter 18, there’s the story of a king finally destroying the bronze snake so people would stop worshipping it.

There is an interesting link with the Greek god Eshmun sar Kadesh, which was a snake god used in medicine. Artefacts show that the Greeks acquired this god from the Phoenicians. The symbol is still used today in some places, of a snake wrapped around a pole (you see them outside pharmacists). Now, what has a snake got to do with medicine? Well, in the Bible account of the Exodus, when the people were leaving Kadesh (Numbers chapter 33) they were being bitten by snakes, and Moses made a bronze snake on a pole and held it up. When the people looked at it, they were saved from the snake bites and lived. After the Exodus, some of them were continuing to worship this bronze snake, saying it was a god of medicine (it’s like these people were continually looking for new gods to worship!) The Bible doesn’t hide that this was happening, and in 2 Kings chapter 18, there’s the story of a king finally destroying the bronze snake so people would stop worshipping it.