A Little Grammar Revision

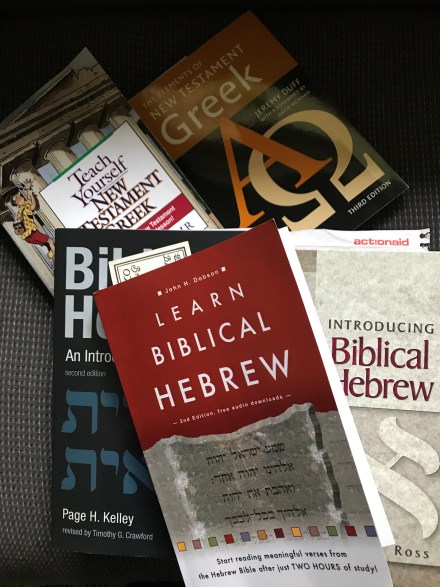

I decided to take a break from my studies this week, and instead to revise some Greek. I started learning Greek in 2020, and I have forgotten nearly everything (‘use it or lose it’ is certainly true with languages). I dug up my two text books—one has a fun but slightly muddled approach,[1] the other an incredibly dry but systematic approach.[2] I read them together, side-by-side, and the knowledge seeped back. However, one of the main things I remember when I started to properly learn a language was my lack of formal English grammar. I went to school in the era of creative writing, when it was all about free expression and writing from the heart and responding emotionally to what we read. I don’t think words like ‘pronoun’ or ‘intransitive verb’ were ever uttered in one of my English lessons. Not ever. Which was possibly an acceptable way to develop a love of words, but not so useful when learning a foreign language.

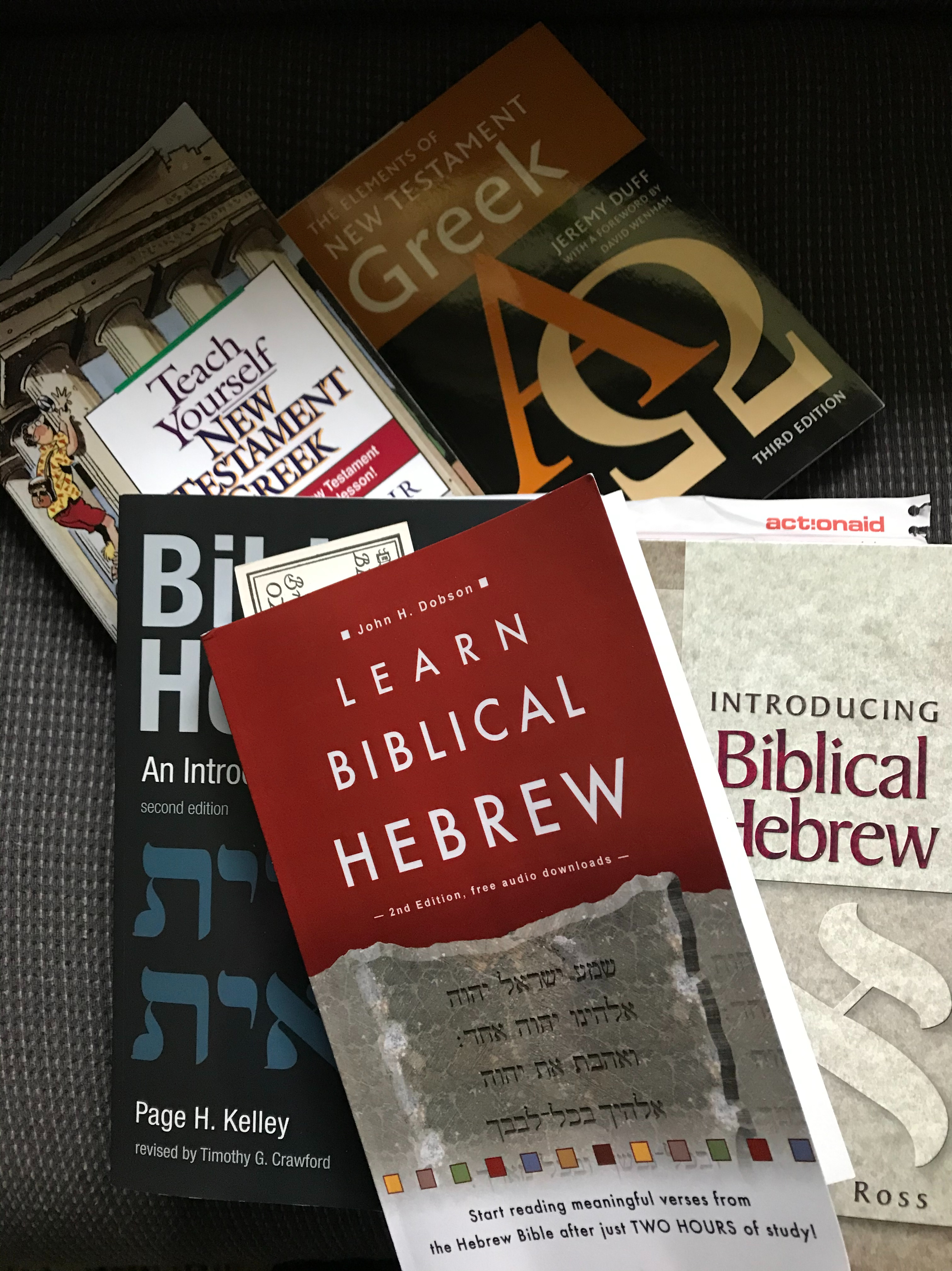

After several years of formal language learning (the Greek, and then the Hebrew) I have now assimilated most of the grammar that I need. But just in case you have never heard these terms, or for the fun of being reminded of them if you were educated in a different era, here are some quick definitions. How many do you recognise?

Nouns

Subject This is the noun that ‘does’ the verb. Eg. The boy arrived. She sang. They ate.

Object This is the noun that ‘suffers’ the verb. Eg. Mary stole the cake.

Common Noun These are things in general. Eg. cup, nose, sky

Proper Noun These are names of people, places, or things. Eg. Jane, Oxford, or Hazelwood School

Abstract Noun These label abstract ideas, actions, states. Eg. Love, peace, destruction

Pronouns

A pronoun replaces a noun with a substitute word. The original word (noun) is the antecedent. Eg. she, it, who, are pronouns which can replace the antecedents: Mum, Meg, Dave.

A relative pronoun (is not your aunty!) but makes a relation (a fancy way of saying ‘a connection’) between clauses. So: ‘John hates Mary. Mary ate the cake.’ This changes to: ‘John hates Mary, who ate the cake.’ Thus ‘who’ is the relative pronoun, and ‘Mary’ is the antecedent.

Adjectives

An adjective describes the noun. We say it ‘qualifies’ the noun. Eg. Greedy Mary ate the cake.

Demonstrative adjectives answer the question: Which noun? Eg. this, those (Greedy Mary ate this cake.)

Possessive adjectives answer the question: Whose noun? Eg. my, your, his (Greedy Mary ate his cake.)

Interrogative adjectives are question words. Eg. Which, where? (Greedy Mary ate which cake?)

Definite article just means ‘the’ and indefinite article just means ‘a’. They are included as adjectives because they qualify the noun. (Greedy Mary ate the cake.)

Prepositions

Prepositions are generally ‘place’ words. Eg. on, in, over. In Greek and English they govern what follows them. So ‘I go into the house,’ the house is what follows the preposition. (In English, they can also do other things, but I am only bothering with the grammar that’s useful for Greek.)

Adverb

An adverb can qualify either a verb or another adverb. They usually end ‘ly’ in English. (Greedy Mary extremely hurriedly ate his cake.)

Verbs

A verb can be an action or a state (thus ‘stative verbs’ –which I am pretty sure never cropped up at my school, where we were only taught that a verb is a ‘doing word’.) Apparently, a ‘state’ is also an action, so if the boy is hot, then his ‘being hot’ is an action and therefore a verb—but a stative one. (I personally feel this is unfair grammar, because ‘the hot boy’ uses ‘hot’ as an adjective, not a verb. Which is very confusing for me, and I am English! My sympathy goes to those who are learning it as a foreign language.)

Transitive Verb A transitive verb effects something (the subject). Eg. They ate the cake. (So ‘ate’ is a transitive verb and ‘the cake’ is the subject—the cake was affected by the verb.)

Intransitive Verbs These do not effect anything else (there is no subject). Eg. I ate. I remain. I die.

Indirect Object This is indirectly affected (a clue in the name!) and usually follow a preposition. Eg. She ate the cake on a plate. (This sentence has a subject: she, a transitive verb: ate, an object: cake and an indirect object: plate.)

Finite Verb This may be indicative, imperative or subjunctive (explained below). A clause must have a finite verb, otherwise it’s a phrase. A complement completes the clause: He is _______. It can be a noun (He is a boy) or an adjective (He is good) or a pronoun (He is mine). In Greek, the complement is never the object, it is always linked to the subject.

Mood

This matters a lot in Greek, but we use it in English too (you just may not be aware of it). Verbs can either be finite or infinite.

Indicative –this is a finite verb, so describes a particular action, and can be a statement or a question. Eg. He went in.

Imperative—this is another finite verb (describes a particular action) and is a command, a ‘bossy verb.’ Eg. Get inside!

Subjunctive—this is another finite verb (describes a particular action) and is a wish, or a wonder.

Eg. I might go inside. Or: If you go inside... [needs to be completed].

Infinitive—an infinite verb, (so not specific, we need more information for it to make sense) a verb that is on-going. Eg. To sing, or to laugh. They tend to follow ‘to’. They are called ‘verbal nouns’ because they tend to follow another verb (I want to sing) like a noun, and they can take an object (to sing a song) like a verb.

While we’re describing mixes (verbal noun) we should also look at participles, a mix of a verb and an adjective.

Participles

Participle—this can be an active participle, which ends in ‘ing’. Eg. laughing, singing.

Or it can be a passive participle, which ends in ‘ed’. Eg. laughed, cried.

Participles are used in English and Greek as adjectives (even though they look like verbs to me!) Eg. The laughing man went inside. You are my beloved mother. (English also uses them as tenses—I am laughing—but Greek does not.)

Tenses

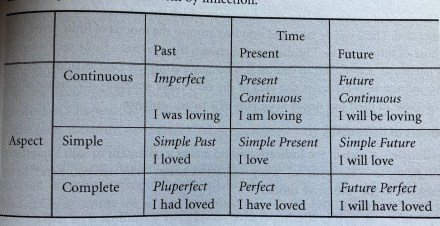

These really confuse me, but Mr Duff included a helpful chart, which I will attempt to copy. Basically, tenses show time (past, present, future) and aspect (continuous, simple, complete). Hold your hat, and we’ll look at some examples: (Depending on the device you read this on, the chart below is either helpful or completely muddled. I have therefore also included a photo, from page 247 of Duff’s book, ref. below.)

Past Present Future

Continuous: (imperfect) (continuous) (continuous)

I was loving I am loving I will be loving

Simple: (simple) (simple) (simple)

I loved I love I will love

Complete: (pluperfect) (perfect) (perfect)

I had loved I have loved I will have loved

If you still have brain left—well done, you are ready to learn Greek. Personally, I am going for a cup of tea and a lie down. Thanks for reading. Hope you have an interesting week.

Take care.

Love, Anne x

******

anneethompson.com

*****

[1] Ian Macnair, Teach Yourself New Testament Geek (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1995).

[2] Jeremy Duff, The Elements of New Testament Greek (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005)